Frequently Asked Questions

At West Michigan Endocrine, the team diagnoses and treats a wide range of conditions. While each patient is unique and every treatment plan is customized, many patients benefit from understanding the practice's approach to common endocrine system issues. And since the best outcomes happen when patients are well-educated about their diagnosis and treatment options, we share some of our expertise in regards to many of these issues below.

Have an endocrine system question not addressed here? Our team welcomes your curiosity and look forward to addressing your question in a future FAQ. Send a secure email to West Michigan Endocrine at contact@westmichiganendocrine.com with your general question. Please do not include any patient-identifying details.

Jump to topics:

What is hypothyroidism?

As an endocrinology practice, we see many patients with hypothyroidism. Hypothyroidism is a condition where the thyroid gland does not make enough thyroid hormone. Our goal in management of hypothyroidism is to help our patients feel better and to follow the American Thyroid Association treatment guidelines for hypothyroidism. Link here for more information. www.thyroid.org has more helpful information.

What causes hypothyroidism?

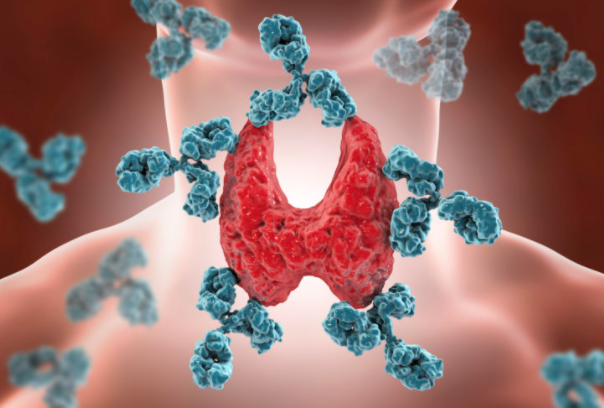

By far and away, the most common cause of hypothyroidism is chronic autoimmune thyroiditis otherwise known as Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Hashimoto's thyroiditis is an autoimmune disease. Autoimmune diseases are diseases caused by your own immune system; instead of the immune system fighting off a virus, for example, the immune system turns on itself. In the case of Hashimoto's thyroiditis, the immune system attacks and destroys the thyroid gland leading to hypothyroidism.

How do you diagnose hypothyroidism?

To diagnose hypothyroidism, we use our patient's symptoms and a lab test called a TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone) to guide our treatment decisions. Our goal is to give patients options. We often check thyroid antibodies, such as thyrogen peroxidase antibodies or TPO antibodies, at the initiation of treatment. We will also frequently check FT4 and FT3 levels at the beginning of treatment to make sure that we have the correct diagnosis. We don't routinely follow TPO antibodies, FT4 or FT3 levels, however, and we don't check reverse T3 levels.

How do you treat hypothyroidism?

We typically treat hypothyroidism with levothyroxine or T4. Generic T4 is called levothyroxine and there are many branded T4 options such as Synthroid and Tirosint. When functioning normally, the thyroid gland makes both T4 and T3 in a ratio of about 14:1. We don't need to take additional T3 because the body converts T4 to T3 in the bloodstream. That said, if patients are still not feeling well after we have optimized treatment with T4, we can consider the addition of T3. Generic T3 is called liothyronine and its brand name is Cytomel.

We do prescribe Armour thyroid and other types of desiccated porcine thyroid, but these preparations are not what we'd recommend first. Armour has a ratio of T4 to T3 of approximately 4:1. This is a lot more T3 than our bodies typically make but if patients feel better on Armour compared to levothyroxine and we are not over-medicating with thyroid hormone, we think Armour is safe to use. We don't think it is safe to use Armour in patients with heart disease or in women thinking about pregnancy or who are pregnant.

What else can help me feel better?

We have no formal training in integrative or functional medicine. However, we believe that inflammation, which is the root cause of Hashimoto's thyroiditis, plays a key role in keeping my patients with hypothyroidism from feeling well.

That said, we've spent quite a bit of time with patients discussing lifestyle strategies to decrease inflammation, such as dietary change; improvement in sleep habits and quality; stress reduction; and restorative exercise. We have also referred patients on occasion to allergy/immunology to look for and eliminate other environmental triggers of inflammation.

How do you handle hypothyroidism in pregnancy?

Ladies! Please tell your doctor if you have hypothyroidism and are thinking of getting pregnant. When you become pregnant, call your doctor right away. We joke with our patients with hypothyroidism that we want to be the third phone call: tell your baby's father, then tell your parents, and then tell us!

So why do we care so much? Our thyroid glands, when functioning well, produce about 50% more thyroid hormone in pregnancy than when we are not pregnant. This increase in thyroid hormone production has already started by week seven and continues to ramp up until week 16 of pregnancy. From the start of pregnancy through week 16 is also when the majority of fetal development is taking place. Thyroid hormone is critical for healthy neurocognitive development. As an endocrinology practice, we like to know before my patient gets pregnant or as soon as she knows that she is pregnant so that we can have the right amount of thyroid hormone on board in early pregnancy.

During pregnancy, we check thyroid function at weeks eight, 12, 16, 20 and 30. We also check six weeks postpartum. Most women can decrease their thyroid hormone doses to their pre-pregnancy dose as soon as the pregnancy is complete.

We do not use Armour thyroid or T3 for our patients who are pregnant or are considering pregnancy. Our thyroid glands produce about 14 times more T4 than T3. As we mentioned before, having enough thyroid hormone is critical for healthy fetal brain development and to avoid pregnancy complications. We know that T3 does not cross into the fetal central nervous system as efficiently as T4 does. That said, if we're treating you with a combination of T4 and T3, such as Armour, you might have plenty of thyroid hormone, but that does not mean that your baby is getting the thyroid hormone that s/he needs for healthy brain development. We hope this explains why we use levothyroxine or branded synthetic T4 in pregnancy.

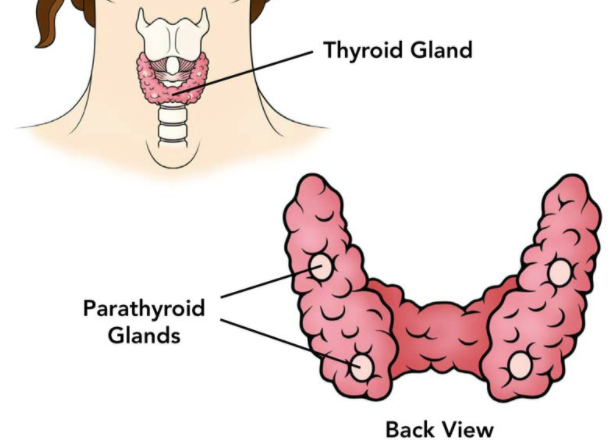

What is hyperparathyroidism?

We're so glad you asked! Elevated parathyroid hormone and problems with bone mineral metabolism are some of our favorites to tackle.

Most of us are born with four parathyroid glands. Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) occurs when too much parathyroid hormone is made inappropriately. This leads to an increase in blood calcium and can cause weakening of the bones, kidney stones, and/or worsening kidney function and symptoms. PHPT effects 0.5-1% of the population and typically occurs in people over age 50. Approximately 85% of the time, PHPT occurs when just one of the four glands produces too much parathyroid hormone and we call this a parathyroid adenoma. Parathyroid cancer can occur but is exceedingly rare.

How do you diagnose and treat hyperparathyroidism?

Before we make the diagnosis of PHPT, we have to rule out other issues that can look like primary hyperparathyroidism but are truly just the parathyroid gland secreting extra parathyroid hormone appropriately to keep calcium balanced in the bloodstream. Vitamin D deficiency, for example, which affects 40% of Michiganders, can cause an appropriate increase in parathyroid hormone.

Once we have definitely made the diagnosis of PHPT, we need to make decisions on treatment. For people who are asymptomatic and don't have any problems with their kidney function, their bones, or kidney stones, we can often just watch and monitor. For those people who are symptomatic or do have kidney disease, have weaker bones, are younger than 50, have very high blood calcium values, or have kidney stones, we do typically recommend treatment. The treatment for primary hyperparathyroidism is surgery. There are other treatments if surgery is not felt to be safe; these treatments lower blood calcium but do not correct the hyperparathyroidism.

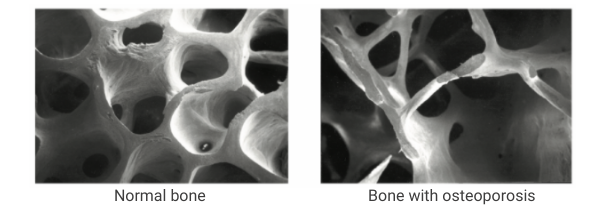

How do you diagnose osteoporosis and mineral metabolism disorders?

You or someone you know likely has osteoporosis, and as an endocrinology practice, we help many people manage it with education, supplements and medication, and exercise. Osteoporosis is a condition where the skeleton becomes less dense and more fragile, increasing the risk for fracture.

Fractures are common: approximately 50% of women and 25% of men over age 50 will have a fracture in their lifetime. And in the elderly, 20% of people who fracture their hip will pass away within 12 months of their fracture. If you’re looking for more information about osteoporosis, the National Osteoporosis Foundation website is a great resource www.nof.org.

We say that someone has osteoporosis when their bone density, which we measure with a DXA scan, falls below a certain point or if the person has a fragility fracture.

Deeming a fracture a fragility fracture can be a little subjective, but we call a fragility fracture one that happens with minimal trauma, like a fall from a standing position. Falling off a roof and having a fracture would not be considered a fragility fracture, but slipping in the kitchen and breaking a hip or a vertebral body would be considered a fragility fracture.

For better or worse, there are not usually symptoms of osteoporosis until there is a fracture. Patients with osteoporosis often ask us if osteoporosis is the reason why their hip hurts, but most commonly hip pain would be from osteoarthritis and unrelated to osteoporosis. The most common form of osteoporosis is postmenopausal osteoporosis or senile osteoporosis.

Before we assume that osteoporosis is related to aging or menopause, which are the most common reasons to have bone loss, we have to rule out other conditions that can cause a low bone density. These include but are not limited to: hyperparathyroidism, vitamin D deficiency, hyperthyroidism, conditions of low blood phosphorus, steroid use, genetic disorders, tobacco use, and autoimmune disease. The list is long. We use our patient’s history and the blood and urine tests to make sure that we have the correct diagnosis.

How do you prefer to treat osteoporosis?

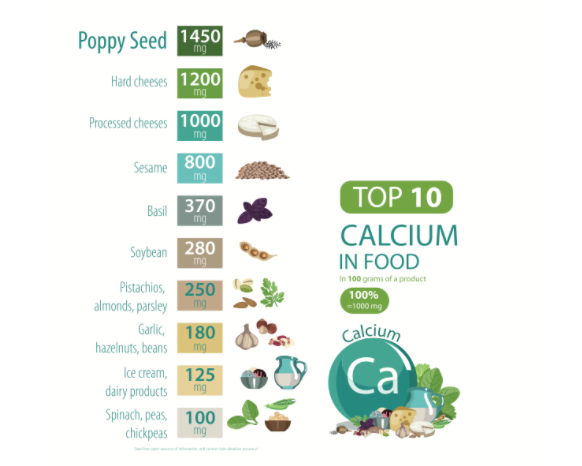

First of all, we cannot overstate the importance of calcium and vitamin D supplementation in the treatment of osteoporosis. Calcium and vitamin D supplementation alone have been shown to decrease fracture risk. The National Osteoporosis Foundation has great patient resources pertaining to how to get and how to calculate dietary calcium. Link here.

Oftentimes, treatments for osteoporosis beyond calcium and vitamin D should be considered. Pharmacologic treatments for osteoporosis can decrease fracture risk by 40-70% and can be divided into two main groups: the antiresorptive agents and the anabolic agents. The antiresorptive drugs include the bisphosphonates (i.e. Reclast, Fosamax, Actonel, Boniva) and Prolia. Reclast is a once-yearly IV infusion and Prolia is given as an injection every six months; the other medicines mentioned are oral. The anabolic agents include drugs like Forteo, Tymlos and Evenity. We consider using these drugs in more severe cases of osteoporosis. These agents are administered as once-daily subcutaneous injections for up to 24 months or once-monthly subcutaneous injections for a total of 12 months. After treatment with an anabolic agent, we need to follow up with an antiresorptive drug in order to maintain the bone strength that we’ve gained while using the anabolic agent.

There are side effects and contraindications to using antiresorptive and anabolic drugs, so each drug needs to be carefully considered for each individual.

The most common side effect that we hear about from our patients receiving Reclast is a flu-like reaction that can occur after the infusion. Fifteen percent of people who receive Reclast have this occur. This reaction should not last longer than 72 hours and is less likely if you come for your infusion well-hydrated.

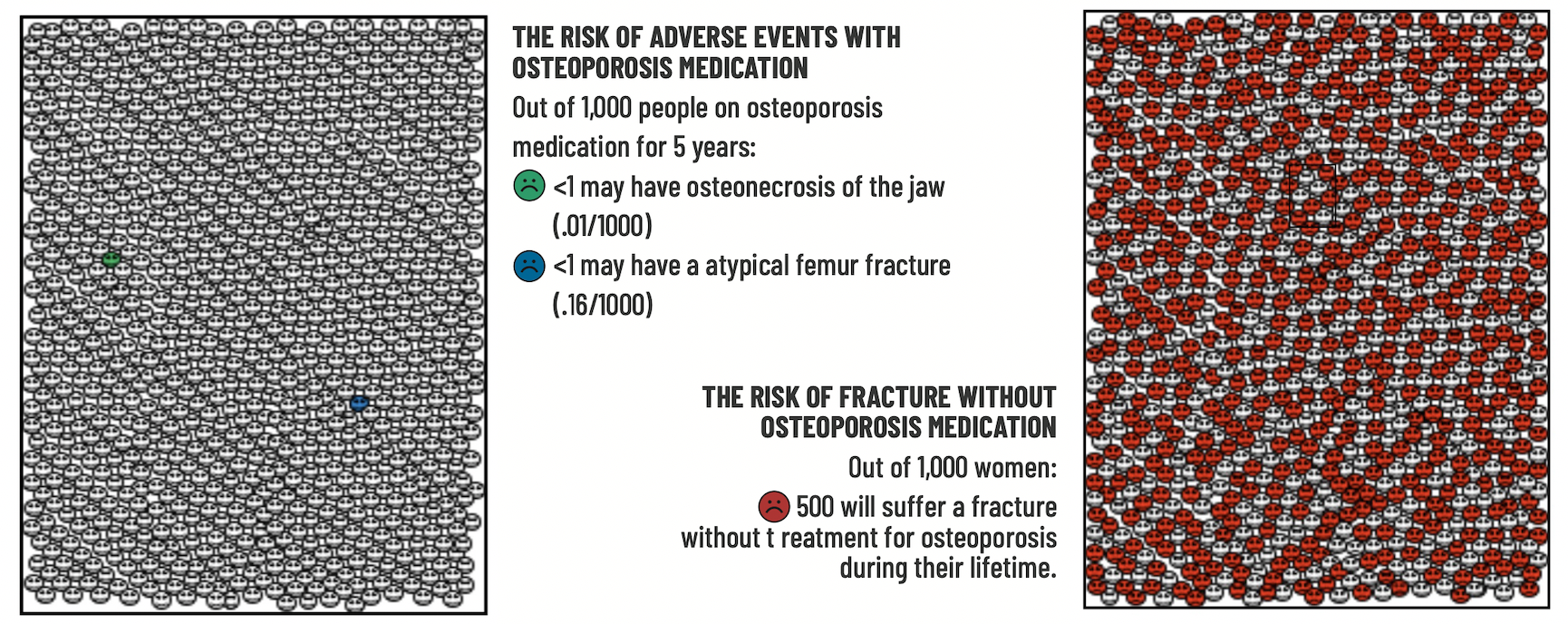

Use of medicines to treat osteoporosis are associated with a problem called osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ). With ONJ, an area of the jaw bone becomes exposed and is difficult to heal. This problem occurs in 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 100,000 people treated. Long-term use of medicines for osteoporosis, without any “drug holiday," can also be associated with atypical femur fractures (AFF). These fractures are typically preceded by aching of the groin or femur (long bone of your thigh). Atypical femur fractures occur in 16 per 100,000 people treated.

This graphic is helpful to depict how likely a fracture is in a person who has osteoporosis and is not treated with medicine versus how likely ONJ and AFF are in people who are treated. On the left side, the green circle depicts how likely a person is to get ONJ if treated, and the blue circle is how likely they are to get an AFF if treated. The right side of the graphic depicts how likely someone is to have a fracture if they are not treated for their osteoporosis.

All patients need to understand the risks associated with the medicines that they're considering, consider the risks associated with choosing not to take a medicine, and make informed choices about what is the right option for them.

We cannot finish this answer without mentioning exercise. Exercise increases bone density and decreases fracture risk. Patients should shoot for at least 30 minutes three days per week and the type of exercise should be something you enjoy. Walking is great for the bones. Fractures typically occur when we fall, so if we can avoid falls, fractures are less likely--much less likely. Exercise reduces fall risk. Strength and balance exercises, such as Tai Chi, have been particularly recognized as beneficial in reducing fall and fracture risk. If our worry for a fall is high enough, then we should consider a formal fall prevention program.

What is a pituitary adenoma?

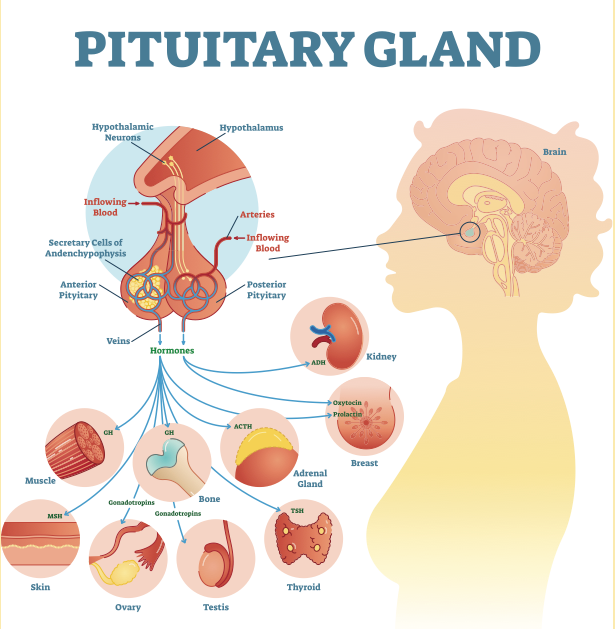

How can such a tiny gland have such a big impact on our health and well-being? We're fascinated by it. The pituitary gland is a pea-sized endocrine gland and is located at the base of the brain. This gland has different cell types that make hormones to control the functions of many other endocrine organs.

Pituitary corticotrophs make ACTH to control the adrenal fasciculata. Pituitary gonadotrophs make LH and FSH to stimulate the gonads. Lactotrophs make prolactin, which men and women both make, and is a hormone important for breast milk production. Thyrotrophs make TSH to control the thyroid gland. And somatotrophs make growth hormone.

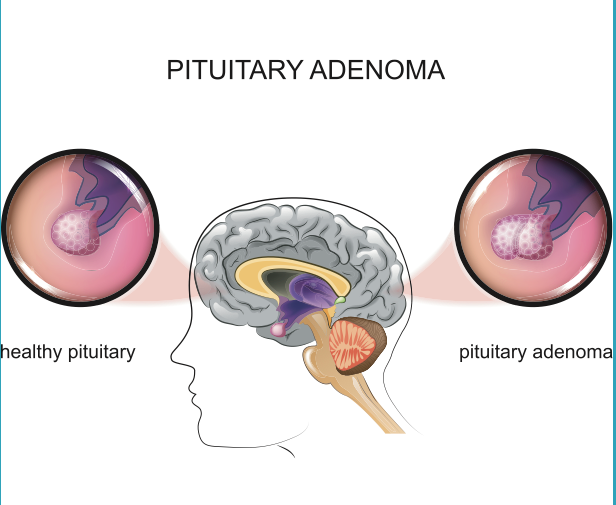

A pituitary adenoma or a pituitary tumor is an overgrowth of one or more of the pituitary cell types. Pituitary tumors are common. In autopsy studies, approximately one in five people were found to have a pituitary tumor. Pituitary tumors are rarely cancerous.

Over 50% of pituitary tumors make prolactin, and we call these prolactinomas. Approximately 30% of pituitary tumors don’t make any hormone, and we call these null cell pituitary tumors. The remaining 20% of pituitary tumors make growth hormone, ACTH, and, rarely, TSH or LH and FSH. Pituitary tumors can cause problems through these hormones that are oversecreted or by compressing the healthy pituitary gland or other structures around it.

When we identify a pituitary tumor, the workup focuses on:

- finding out if the tumor is making any hormone;

- making sure the rest of the pituitary gland is functioning the way that it should; and

- monitoring for growth of the pituitary tumor.

As above, the most common pituitary tumor is a prolactinoma and this is treated with an oral medicine called cabergoline or bromocriptine. For larger pituitary tumors or for those making hormones other than prolactin, surgery is typically indicated. For many of our patients, who have a small tumor and normal pituitary function, we can just monitor with labs and with periodic imaging of the pituitary.